I’ve noticed some Industrial Automation vendors on Twitter recently (not to mention some automation related magazines).

I like that trend, but here’s some commentary on who’s doing what right and wrong (from an engineer’s perspective anyway):

I’ve noticed some Industrial Automation vendors on Twitter recently (not to mention some automation related magazines).

I like that trend, but here’s some commentary on who’s doing what right and wrong (from an engineer’s perspective anyway):

After my recent rant about Rockwell Automation and their frustrating online support, I received an email from Joe Harkulich, Global Quality Leader at Rockwell Automation. The first thing he did was, helpfully, get me straightened out with my TechConnect ID. Apparently the one we were given wasn’t our real TechConnect ID, and it happened to be the ID of another company in Mexico, which caused some confusion on my end. Once that got straightened out, I could access the article I was looking for (a bit late, but better than never).

Joe then invited me to join a conference call with Esther Beris (Rockwell Knowledgebase), Jon Furniss (TechConnect), and Rob Snyder (Senior Manager for Rockwell’s remote support). I’m thankful for them taking the time to do this, as I’m really only a moderate user of Rockwell Automation products. (I really don’t think they’re very concerned about my legions of blog readers and twitter followers). I’ll relate a few of the details of the call here, and I really want to express my gratitude to everyone involved for their time.

The first item on the agenda was Joe addressing some misinformation in my previous blog post. I had made a comment about Beckhoff’s 350MB knowledge-base available for download, and I had suggested that Rockwell should do something similar. It turns out that Rockwell does offer TechConnect subscribers the ability to receive 3 DVD’s full of all their product manuals and their entire knowledge base. Joe offered to send me a copy, and I accepted. I received them yesterday and installed them on the laptop at work. This will be nice pending an on-site trip that’s scheduled next month. I’m a bit concerned that the discs are dated May of 2008. I was expecting them to be about 6 months old. We did discuss the idea of making them automatically download updates of the knowledge base, etc., so your offline copy is always up to date, but they pointed out that this would be a huge amount of information so it probably couldn’t happen, but they would take the idea into consideration. Personally I think a solution like that would have a lot of value.

We then turned our discussion towards some of the issues I had raised with Rockwell’s online support in my previous post. I certainly made it clear that I have always been impressed with Rockwell’s paid telephone support, and I really have nothing to complain about there; they are simply awesome! When it comes to the online support, we talked about these issues:

It makes no sense to me why you have to sign on separately at www.rockwellautomation.com and at their knowledgebase. Apparently it doesn’t make a lot of sense to the folks at Rockwell either, and they’re working on it. However, there’s no time-line for the resolution of it (or at least they couldn’t give me one). I think it’s one of those cases where the politics of a big organization are getting in the way of doing something really simple, and I can appreciate that. I did get the impression that the people involved do care, and it will get done, eventually.

In past years I would frequently do a lot of automation work, and then switch to PC programming for a project or two, and then switch back to automation work as I’ve recently done. I always found it a bit frustrating the first time I tried to download some EDS file and Rockwell had canceled my account because it had been longer than 6 months since I’d signed in. Apparently I’m not the only customer to complain about this, and Rockwell is in the process of changing this. Bravo!

Let’s say I go to the ControlLogix Product Page. On a normal website when I look at a product I see exactly what that one component looks like, a link directly to the datasheet or user manual, a tab with all the specs on it, and all the information I need to buy that product. But the ControlLogix page is a brand page, not a product page. It’s almost completely useless to me as an Engineer. There is a Literature link, and that has a selection guide and something else, but then it tells me I have to go to the literature library to find all the good documentation.

When I explained this on the conference call I got some good laughs, because again, I’m not the first person to complain about this. Apparently this is being resolved, and they do have a time-line: September 2010. That’s great news and I’m really happy to hear it.

I’m afraid the issue of paid vs. unpaid content is still a sticking point for me. They explained to me that they chose a paid model for their support because they can provide better support. There’s no question in my mind that the quality of Rockwell’s telephone support comes through time and again, but I have to disagree with the pay-wall model they’re using for online support. I really think what’s happened is that the technical support group within Rockwell is literally scared of what could happen if they didn’t maintain a strangle-hold over the information that guys like me need to do their job.

I’ve talked before about vendor lock-in in the industrial automation industry, so I’m not going to go into that again. But this is a case where a company is selling me upwards of $10,000 of automation equipment per project and once they’ve done that, they want to charge me extra for access to the information I need to make it work the way it was supposed to work in the first place. I understand the paid telephone support model because there’s a one-to-one relationship between the amount of time I spend on the phone and the amount of time they have to pay someone to talk on the phone. But while they’re doing that, they’re already creating a knowledge-base of information. As smarter people than I have pointed out repeatedly, the marginal cost of distributing that electronic information to one more person is as close to zero as humanity has ever seen. No, you don’t have to because copyright is always on your side, but if you don’t, you open yourself up to being undercut by the following business model:

…which is exactly what ControlsOverload is. Remember in my last post where I said that I took 3 minutes of my own time and posted the question and answer related to my problem at ControlsOverload? Check out what happens when you search for compactlogix type 01 code 01 fault or even compactlogix powerup fault. The first item in the search results is my question and answer. You can even go to that page and add more information, or correct inconsistencies and you don’t even need to sign-up!

Rockwell has one group that makes products and another group that charges people for support on those products. In order to protect the revenue model of the second, they put barriers in place to maintain a monopoly on information, even though every single industry that has relied on maintaining a monopoly on access to information is dying a slow miserable death. Meanwhile I wasted another hour of my time trying to get a product I’d already purchased to work, and they had the information to cut that time down to 2 minutes, but they put all these barriers in my way even though I’d already paid for support!

The price to hire a PLC programmer is anywhere from about $50 to $100 an hour in my experience. Let’s say $75. Every time Rockwell’s support barriers waste an hour of my time, the total cost of ownership of their equipment goes up by, on average, $75. On top of that, it frustrates me enough to blog about it, and there’s an opportunity cost as well. I could have been using that hour to improve the efficiency of the machine in some other way rather than fighting with Rockwell’s internet site.

Here’s my suggestion to Rockwell to fix the situation:

What do I mean by paid premium content? Tutorials. Training videos. Example applications. Code review services (a support person can review your automation program and offer advice). E-books. Insider news & tips. Access to beta versions of upcoming software releases. In short, something I’m willing to pay for above and beyond what I believe I’ve already paid for.

Good luck Rockwell – the next few years are going to be interesting.

I’ve decided to create a tutorial for beginners getting started with RSLogix 5000 from Rockwell Automation. Part 1 is already posted: Creating a New Project. I will be filling in the rest over the next few weeks. I hope new automation graduates and experienced members of the automation industry who are migrating from another platform will both find something useful.

As always, I welcome any and all constructive feedback.

I recently had a problem with an Allen-Bradley CompactLogix processor. The power went out, came back on, and the processor had faulted with a major fault, type 01, code 01. The fault message said “Power lost and restored in RUN mode”. There must be a way to disable this fault, and just have it go back into run mode so the operator can recover.

I Googled for the fault message and I got a link to a helpful forum thread. In that forum thread there was a link to a Rockwell Automation Knowledgebase Article that seemed to have the information I was looking for. I clicked the link and it told me I needed to login. That’s annoying enough, but fine. I tried my normal username and password for such sites, and that didn’t work. I went into my encrypted file and pulled out the username and password I’d saved for Rockwell Automation. That didn’t work.

Ok, fine. It had an option to email me my user name. I waited a few minutes for the email – yes the username I was using was OK. I clicked on the option to reset my password. Got the email, reset the password to the one I had saved anyway. Success! I was logged in, but it had forgotten what article I was trying to get to, so I went back to the original forum post and clicked the link again. “This article has been locked, or …” blah blah blah about a TechConnect ID. Ok, so I go to my profile page and click on the tab for TechConnect support IDs. None registered. Hmm, no obvious way to register one. I go to the other profile page… TechConnect ID… excellent! I enter that, click save, and now it needs my company name, address, etc. Ok, I enter that… but now I can’t click save. I have to go backwards, re-enter the TechConnect ID, and my company name and address, and then it saved. Ok, great!

I go back to the forum and click the link again. “This article has been locked, or …” What?!? I check my list of TechConnect IDs again, and there’s nothing there. This is really annoying me at this point. Oddly, under my name it now has the name of some Mexican company, and some place in Mexico. I check my profile page again and it all looks right, and I double-check the TechConnect ID. It’s right (and I know it’s right because I’ve used it to call Rockwell tech support recently).

I go back to Google and search again for the fault code, and I see a link to the Rockwell knowledge-base article. I click on that… same message! What’s going on here? How can Google even index a page that’s behind a sign-up wall and doesn’t even show you the page unless you have a valid TechConnect ID?

Going back to the original forum post, I did find some useful information in there, but obviously the knowledge-base article would have helped me the most. How far behind is Rockwell Automation’s online support? They’re still in the 90’s. I realize there are still a lot of people in this industry who are happier to pickup a phone and call their phone support in a situation like this, but as time goes on and the Millennial Generation continues entering the workforce, self-help focused people like myself are going to be more and more commonplace. We won’t settle for getting our questions answered in hours or even 30 minutes anymore; we want to solve our stupid problems like this in minutes or even seconds, and the technology is there to let us do it. Stop putting unnecessary barriers in our way! Rockwell Automation online support: FAIL!

By the way, I just spent 3 extra minutes and entered my technical question and answer over on ControlsOverload, a website for technical questions and answers about industrial automation. A website where you don’t have to sign in, and nothing is ever blocked behind any kind of wall. If Google can see it, so can you. This is the future of finding information on the internet. Rockwell Automation: Make it easy for me to use your hardware, and maybe I’ll buy more! You know what… here’s Beckhoff’s whole 350MB knowledge-base available for download so you can take it with you onsite when you don’t have an internet connection. Brilliant isn’t it? It’s called openness and it’s the new name of the game. Wake up!

Update (9 MAR 2010): The Global Quality Leader from Rockwell has contacted me and it looks like we’re going to have a constructive discussion about some of these issues (and he also gave me a different TechConnect ID to try). +1 to Rockwell for having their ears on!

Update (20 MAR 2010): I posted a write-up on Rockwell’s response here.

I’ve been working on an HMI application recently (RSView ME). At the end of the day I saved everything, closed the project, then used Application Manager to backup the application to an .apa file and store it on the server.

This morning I opened the local copy of the application, and a significant portion of the work I had done yesteday was “undone”. It was only one of the displays, but all of the changes were missing. I restored a copy of the backup, and it was the same there. Now I’m pretty paranoid about saving my work, so I probably saved that display about 50 times yesterday, and it was definitely saving somewhere. The question was, where?

Here’s what I did to get myself into this problem:

- Started by copying one display (let’s say “A”) to make a new one (let’s say “B”).

- I then renamed the duplicate (let’s say from “B” to “C”). I probably didn’t close the display before renaming it (which might have caused the problem).

- I made all of my changes to the display, saving along the way.

It turns out that the changes I made were being saved against “B”, not “C” even though “B” didn’t really exist anymore. I was able to recover from this problem with the following procedure:

- Close the application (but leave RSView Studio open if you want)

- Goto C:\Documents and Settings\All Users\Documents\RSView Enterprise\ME\HMI projects\[proj-name]\Gfx

- Rename C.Gfx to D.Gfx

- Rename B.Gfx to C.Gfx

- Open the application again in RSView Studio. The changes should be restored.

I hope that helps someone one day. 🙂

Recently someone asked me what the difference was between PLC programming and PC programming. This was a topic I’ve talked about before, and I gave him the same old answer I’d already come up with, but it got me thinking about it again.

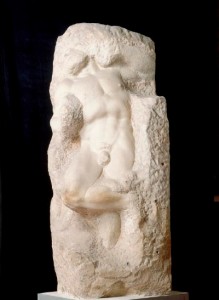

Now I have a new way to compare PC programming and PLC programming: PC programming is like brick-laying and PLC programming is like sculpting.

When you write a PC program, you start out by writing the least amount of code you can to get a functional program. You run and debug that. You check it in to source control, and then you repeat the cycle, building a little more, testing it, and at regular intervals you show it to a customer, get feedback, and change direction, but you always work in small increments because it’s easier to build it that way. You make sure you’ve built a solid foundation, and then you build more on top.

On the contrary, the first time you download a PLC program to a new machine, you have a fixed number of outputs that you have to account for. You can’t just program one axis of motion first without taking into account the position of other axes on the machine (unless you enjoy the sound of metal deforming). So you start by writing logic for all the outputs and you load on more and more conditions that prevent the motion from occurring until you’re absolutely sure that nothing will move unless it’s absolutely safe. Of course, when you download this program to the machine, nothing moves, no matter what buttons you push. This is actually a good place to be. In some cases you actually put conditions in that you know could never be true, just to make sure nothing will move until you’re really sure you want it to.

On the contrary, the first time you download a PLC program to a new machine, you have a fixed number of outputs that you have to account for. You can’t just program one axis of motion first without taking into account the position of other axes on the machine (unless you enjoy the sound of metal deforming). So you start by writing logic for all the outputs and you load on more and more conditions that prevent the motion from occurring until you’re absolutely sure that nothing will move unless it’s absolutely safe. Of course, when you download this program to the machine, nothing moves, no matter what buttons you push. This is actually a good place to be. In some cases you actually put conditions in that you know could never be true, just to make sure nothing will move until you’re really sure you want it to.

In a letter from 1549, Michelangelo defined sculpture as the art of “taking away” not that of “adding on” (the process of modeling in clay), which he deemed akin to painting. (Reference)

Now that you’ve downloaded your logic to the PLC, debugging and commissioning the machine is largely a matter of taking away those conditions that you didn’t really need. This is done one motion at a time until the machine does exactly what you want, when you want, but only that. Your PLC program is done, not when there’s nothing left to add, but when there’s nothing left to take away.

That is, until you add a data collection system…

(This is the third part of a trilogy of blog posts about what I think is the biggest roadblock preventing significant growth in the industrial automation industry. You should read Part 1: Industrial Automation Technology is Stagnant and Part 2: Why Automation Equipment Vendors Dabble in Integration first.)

I was recently making significant additions to a PLC program and the resulting program was too big to fit in the existing PLC. There weren’t many areas where the code could be made smaller without impacting readability, so I went out and priced the same series of PLC with more memory. I’m not going to name brands or distributors here (and I’d probably get in a lot of trouble if I did, because they don’t publish their prices), but I was taken aback by one thing: the only difference between these two controllers was the amount of memory (execution speed and features were the same), and it was over $1000 more. I realize this is “industrial” equipment, so the memory probably has increased temperature ratings, and it’s battery backed, but how much PLC memory can you buy for $1000? As of writing this post, the cost of 1 Gibabyte of memory for a desktop computer is less than $50.

At $50 per Gig, 20 Gigs of PLC memory? Nope.

Ok, it’s industrial, so… 1 Gig? Nope.

Try less than half a Megabyte. Yes.

Just for the sake of comparison, how much is that per Gigabyte? If half a Meg costs $1000, then the price of PLC memory is 2 Million dollars per Gigabyte. WTF? It’s not 40 times more expensive, it’s forty thousand times more expensive than commodity RAM.

Do you know why they charge two million dollars per gigabyte for PLC memory? Vendor lock-in. It’s that simple. They can charge thousands of dollars because the switching costs are insanely high. I can either buy a PLC in the same series from the same manufacturer (and they make sure there’s only one distributor in my area) with more memory, or I can replace the PLC with one from another manufacturer incurring the following costs:

So it really doesn’t matter. They could charge us $5000 for that upgrade and it’s still cheaper than the alternative. Why don’t they publish their prices? Simple, they price it by how much money they think you have, not by how much it costs them to produce the equipment. Wouldn’t we all like to work in an industry like that?

How did it get this way? In the PC industry, if Dell starts charging me huge markups on their equipment, I can just switch to another supplier of PC equipment. Even in the industrial PC world, many vendors offer practically equivalent industrial PCs. You can buy a 15″ panel mount touch screen PC with one to two gigs of RAM for about $3000. Add $500 and you can probably get an 80 Gig solid state hard drive in it. Compare that with the fact that small manufacturing plants are routinely paying $4500 for a 10″ touch screen HMI that barely has the processing power to run Windows CE, and caps your application file at a few dozen megabytes!

The difference between the PC platform and the PLC platform comes down to one thing: interoperability standards. The entire explosive growth of the PC industry was based on IBM creating an open standard with the first IBM PC. Here’s the landscape of personal computers before the IBM PC (pre 1980)*:

Here’s the market share shortly after introduction of the IBM PC (1980 to 1984):

… and here’s what eventually happened (post 1984):

Nearly every subsystem of a modern PC is based on a well defined standard. All motherboards and disk drives use the same power connectors, all expansion cards were based on ISA, or later PCI, and AGP standards. External devices used standard RS232, and later USB ports. Hardware that wasn’t interoperable just didn’t survive.

That first graph is exactly like where we are now in the automation industry with PLCs. None of the vendors have opened their architecture for cloning, so there’s no opportunity for the market to commoditize the products. Let’s look at this from the point of view of a PLC manufacturer for a moment. Opening up your platform to cloning seems like a really risky move. Wouldn’t all of your customers move to cheaper clones? Wouldn’t it drive down the price of your equipment? Yes, those things would happen.

But look at what else would happen:

Why don’t we have open standards? What about IEC-61131-3? PLC vendors tell us that their controllers are IEC 61131-3 compliant, but that doesn’t mean they’re compatible. The standard only specifies what languages must be supported and what basic features those languages should have. Why didn’t the committee at least specify a common file format? You may be surprised to learn that many of the major committee members were actually from the PLC equipment manufacturers themselves. The same people who have a vested interest in maintaining their own vendor lock-in were the ones designing the standard. No wonder!

What about the new XML standard? Well, it’s being specified by the same group and if you read their documentation, you can clearly see that this XML standard is not meant for porting programs between PLC brands, but rather to integrate the PLC programming tools with 3rd party programs like debugging, visualization, and simulation tools. You can be certain that a common vendor-neutral file format will not be the result of this venture.

I see three ways this problem could be solved:

Option 1 is almost doomed to fail because it has the word committee in it, but options 2 and 3 (which are similar) have happened before in other industries and stand a good chance of success here.

In my opinion, the most likely candidate to fulfill option 2 is Beckhoff. I say this because they’ve already opened up their EtherCAT fieldbus technology as an open standard, and their entire strategy is based around leveraging existing commodity hardware. Their PLC is actually a real-time runtime on a PC based system, and their EtherCAT I/O uses commodity Ethernet chipsets. All they would really need to do is open source their TwinCAT I/O and TwinCAT PLC software. Their loss of software license revenue could be balanced by increased demand for their advanced software libraries in the short term, and increased demand for their EtherCAT industrial I/O in the longer term. Since none of the other automation vendors have a good EtherCAT offering, this could launch Beckhoff into the worldwide lead relatively quickly.

For option 3, any company that considers automation equipment to be an expense or a complementary product (i.e. manufacturing plants and system integrators) could do this. There is a long term ROI here by driving down the cost of automation equipment. Many internet companies do this on a daily basis. IBM sells servers and enterprise services, which is the natural complement of operating systems, so they invest heavily in Linux development (not to drive down the cost of Linux – it’s free – but to offer a competitive alternative to Microsoft to keep Microsoft’s software costs down). Google does everything it can to increase internet usage by the public, so it invests heavily in free services like Google Maps, Gmail, and even the Firefox web browser. The more people who surf, the more people who see Google’s advertising, and the more money they make.

If I were going to go about it, I’d build it like this:

If you did that, anyone could make hardware that’s compatible with this platform, people are free to innovate on the runtime, and anyone can make improvements to the programming environment (as long as they give their changes back to the community). Instant de-facto standard.

I know some of you may be grinning right now because this is the path I’m following with my next personal software project, that I’m calling “Snap” (which stands for “Snap is Not A PLC”). However, Snap is for the home automation industry, not the industrial automation industry. If any company out there wants to take up the gauntlet and do this for industrial automation equipment, you may just change this industry and solve our biggest problem.

Discussion is welcome. Please comment below or contact me by email (e8pzrhs02@sneakemail.com).

* Graphs courtesy of ars technica.

(This is part 2 of a trilogy. You should read Part 1: Industrial Automation Technology is Stagnant first, and then you can read the thrilling conclusion: Lowering the Cost of Automation Equipment.)

Tell me if this sounds familiar… you’re a systems integrator and you’ve been asked to come and bid on a project. At the bid line-up meeting, you sit down in the meeting room, and you look across the table, and there’s someone from the equipment vendor XYZ’s integration services department.

Of course the customer has specified that you have to use equipment from vendor XYZ, and of course the integration services wing of vendor XYZ can purchase this equipment internally (at a discount) so they can obviously undercut your price. This always left a bad taste in my mouth, but thankfully some vendors have stopped doing this.

But ask yourself why they would do this in the first place. Integration is a cut-throat market and the margins in the equipment business are significantly higher than doing integration. What business sense does it make to expand into a low margin market and risk annoying the very companies who are out there pushing your product to the end customer?

Everyone knows the economic principle of supply and demand. If supply goes up, price goes down, but if demand goes up, price goes up. That explains what happens when equipment vendors offer integration services and undercut the competition: the supply of integration services goes up, and prices go down. This is their goal. This bears repeating: Their goal is to reduce the price of integration services in general.

Let’s talk about competitive products vs. complementary products for a moment. When a competitor lowers their price, you have to lower yours, but when the price of a complementary product goes down, demand for your product goes up, and therefore the price of your product goes up. What are complementary products? They’re products that are often purchased together, like razors and razor blades, cars and gas, or even automation equipment and integration services.

Gillette made a fortune realizing that if they reduced the price of razors, the demand for blades would go up. When the price of gas goes down, people buy bigger cars. Likewise, the automation equipment vendors know that if they can reduce the price of integration services, the demand for automation equipment will go up, and they can charge more for their product.

While I appreciate the value of competition, it needs to be a fair market. By choking off integrators, the vendors are just promoting a race to the bottom of quality.

Personally, I don’t think it has to be this way. In future posts I’m going to discuss things that the integration industry can do to reverse this trend and stop the downward spiral.

Thinking back to my childhood, I find it odd why I remember some memories so vividly while most are lost to time. I have this one absolutely clear memory. I was walking home with my mother (most likely carrying a rented copy of Star Wars or Empire Strikes Back from the local video store, which was a novelty at the time). I must have been going on about something I read about robots… I think I got a book about robots around that age and I saw pictures of some of the first industrial robots of the time. Anyway, I can clearly remember my mother telling me that she was afraid everyone was going to lose their job to a robot soon.

I think the reason this memory stuck with me was how contrary it was to the culture of kids at the time. We idolized robots. The coolest things in our lives were droids, AT-ATs and Transformers (my, how things have changed, eh?). But this wasn’t over-the-top paranoia, it was the generally accepted truth at that time. For the most part, those anxieties have vanished along with fears of nuclear war, only to be replaced by new anxieties of terrorism.

The truth is that we’ve been replacing people with robots for the last quarter of a century, and the unemployment rate peaked in the early 80’s and has been going down, not up! How is it possible that unemployment has fallen while automation is rising?

A History Lesson

In 1865, William Stanley Jevons published a book called The Coal Question. “In it, Jevons observed that England’s consumption of coal soared after James Watt introduced his coal-fired steam engine, which greatly improved the efficiency of Thomas Newcomen’s earlier design … Jevons argued that any further increases in efficiency in the use of coal would tend to increase the use of coal. Hence, it would tend to increase, rather than reduce, the rate at which England’s deposits of coal were being depleted.”

This effect became known as the Jevons Paradox:

In economics, the Jevons paradox … is the proposition that technological progress that increases the efficiency with which a resource is used, tends to increase (rather than decrease) the rate of consumption of that resource. It is historically called the Jevons Paradox as it ran counter to popular intuition. However, the situation is well understood in modern economics. In addition to reducing the amount needed for a given use, improved efficiency lowers the relative cost of using a resource – which increases demand and speeds economic growth, further increasing demand.

Automation Increases the Efficiency of Human Resources

Workers are a resource too. Automation is just a technological means to improve the efficiency of people, allowing one person to do the work of many. Since there is no cap on the demand for work, automation increases the demand for workers, since each worker becomes more valuable. Hence, unemployment goes down and wages go up.

ControlsOverload Improves Your Efficiency

When I first got into controls, you learned everything by reading a paper manual (if you could find one) or by trial and error, or if you were lucky, from someone else in your company who had used this technology before. We wasted hours trying to figure stuff out, but we accepted this because it was normal. But it also made us inefficient.

Google came along but largely passed us by. Vendors keep their knowledge bases behind locked doors on the internet, and when working on the plant floor, we rarely had internet access anyway, but that’s changing. Many of us now have smartphones so we can access the internet from anywhere. Sometimes we even have WiFi.

Enter ControlsOverload, Web 2.0 meets Controls Engineering. You don’t need to pay anyone to join. You don’t even need to register to ask or answer a question. It asks that you leave your name, email address, and website, but you can make these up if you want to remain anonymous.

When you start typing your question into ControlsOverload, it automatically searches the existing questions to see if it’s already been asked. As the amount of content on the site grows, the chance that you’ll get your answer immediately grows as well. If the question hasn’t been asked before, posting your question is a single click away. When you get answers, registered users can vote them up or down. The best answers rise to the top, so you don’t have to search through 7 pages of forum posts to find the most relevant or correct answer.

Questions are also “tagged” by technology. Perhaps you’re a vendor and you want to see all the questions related to your products. Here’s the page for all Allen-Bradley technologies for instance. If you want, you can subscribe to the RSS feed for the same page.

Will it work? The technology is already a huge success story for traditional PC programming, along with other topics like parenting and personal finance. It works. People participate because it’s really useful.

The point of ControlsOverload is to make us more efficient, as an industry. We waste less time figuring out how to do the simple stuff, like how to copy symbols out of a PLC into Excel and vice-versa.

Doesn’t this mean we’re giving away our valuable knowledge for free? Are we essentially automating ourselves out of a job?

There’s no doubt our jobs will change. We will spend less time doing trial and error and more time solving customers’ problems. The customer doesn’t care about editing PLC programs; they care about making their facility more efficient. If we can solve that problem faster and easier, then we’re more efficient. If we’re more efficient, the demand for our services goes up.

Whether you participate or not, ControlsOverload is going to increase the demand for controls engineers, and that’s going to increase the wages of controls engineers. ControlsOverload will make you more money.

On the other hand, if your business strategy is to be the only one on the block who remembers the arcane technical details of a Fanuc RJ3iB controller, I’m sorry to tell you that the viability of that business model is quickly being exhausted.

Join us on ControlsOverload:

(This is part 1 of a trilogy. When you’re finished reading this, you can read Part 2: Why Automation Equipment Vendors Dabble in Integration and Part 3: Lowering the Cost of Automation Equipment.)

I’m not the first person to notice that industrial automation technology isn’t keeping up with the rapid pace of technological change that we’ve all grown used to. Jim Pinto commented on it years ago:

Industrial automation business seems to be stuck in the mold of being a slow-growth, stable business. This generates a mindset, perhaps even complacency that inhibits change. In my opinion it’s marketing myopia, an unwillingness to think “outside the box”.

Most major automation companies have gross-profit margins of 40-50%, the industry mindset. Many other large companies in other businesses generate much lower gross margins, in the region of 20-25%. Some of this may be accounting differences, but the broad-brush differences are there. Traditionally, automation business is based on higher gross margins and lower net-profit, and it’s difficult to think outside that box.

In the industrial market, only 2-3% is spent on R&D, with some lower than that. By contrast, many of high-tech manufacturers spend 10-15% – Cisco 15-20%, with HP, Lucent, in the 8-10% range, and Motorola and Ericsson at 10-15%. One wonders what the impact would be, if industrial automation companies doubled, or even tripled, their R&D investments.

How is it that an industry like industrial automation equipment can have margins in the 40 to 50% range when their primary customers are manufacturers, probably the most price-conscious market in the world today? I’ll tell you why: they’re smart. Here’s what they did…

Originally they all sold interchangeable parts. You built a control system out of power supplies, relays, terminal blocks and valve banks. All of these parts are available, in replacement form, from various manufacturers and distributors so competition keeps margins tight. Even if you only used P&B relays, it’s pretty easy to switch your standard to Phoenix if you can get a better deal.

Then they came out with something revolutionary: the PLC. Manufacturers jumped on it because you could take four double-door panels worth of relays and replace it with a single unit, and even reprogram it in real time! It was truly a marvel of technology, but it shifted the balance of power in the industry away from the customers and towards the vendors. Now this single piece of equipment that controls the assembly line isn’t interchangeable with other vendors. Not only that, but it requires expensive programming software, not to mention a steep ramp-up time for the maintenance and engineering departments to learn the technology. Manufacturers started standardizing on “automation platforms”. Obviously this creates vendor lock-in. Once you standardize on one technology, the vendors can pretty much count on your continued business as long as they provide good support and a clear upgrade path. The barrier to switching technologies is so great that vendors can afford to have high margins, and they don’t feel the pressure to innovate like in other markets.

Unfortunately this means manufacturers are losing. They’re not getting as much value for their money as they could be. Here are some examples of what a PLC should be able to do as we approach the year 2010 (but can’t):

Another unfortunate side effect is reduced innovation in the system integration space. Let’s say you’re a system integrator and you want to develop some product for a niche market, you have to choose an automation technology to base it on. Once you’ve chosen that controls technology, say Allen-Bradley, you’re also locked in. You’re going to find it hard to sell your product to a customer that has standardized on Siemens, which means you have to invest extra effort, money, and time in re-engineering your product to work on their platform. Worse, their platform may not have all the features that your product requires, so it may not work as well. It’s not much of a product if you have to re-work the design every time, which means it’s harder to recoup your development cost.

Ultimately, automation technology is more expensive and less powerful because automation equipment vendors have stopped innovating.